The origin of the Olympics

Studying the Olympic Games from the perspective of cultural studies is fascinating; we can understand how the Olympics are more than sporting achievements, because they are connected with so many other aspects of our lives and culture. Let’s think, for example, about running, and its links with history, language, ceramics, politics and equal rights.

The Olympics probably began 2797 years ago, in Olympia in ancient Greece. At first there was just one event, running. The athletes ran a set distance along a straight track, probably about 180 metres. This distance was known as a stade, and the word stade became associated with the place that races were run. This is why our modern sports facilities are known as stadiums in English and スタジアム in Japanese.

Much of our knowledge of the ancient Olympics comes from the scenes depicted on ancient ceramics, such as the runners in the illustration. The relaxed position of their arms shows that these men are long distance runners. They run naked, displaying the beautiful bodies they have exercised hard to hone, because the ancient Olympics were a religious festival to honour Zeus, king of the gods, to whom only the most perfect offerings could be made.

Running the marathon

The marathon is now one of the iconic events of the Olympics, although it did not exist in the ancient Olympics. After a break of about 1,500 years the Olympics were revived in modern times in 1896 by Baron Pierre de Coubertin of France. Wishing to honour Greece as the place of origin of the Olympics, his committee chose Athens to host the first modern Olympics, and in addition devised the marathon race as another acknowledgment of Greek culture.

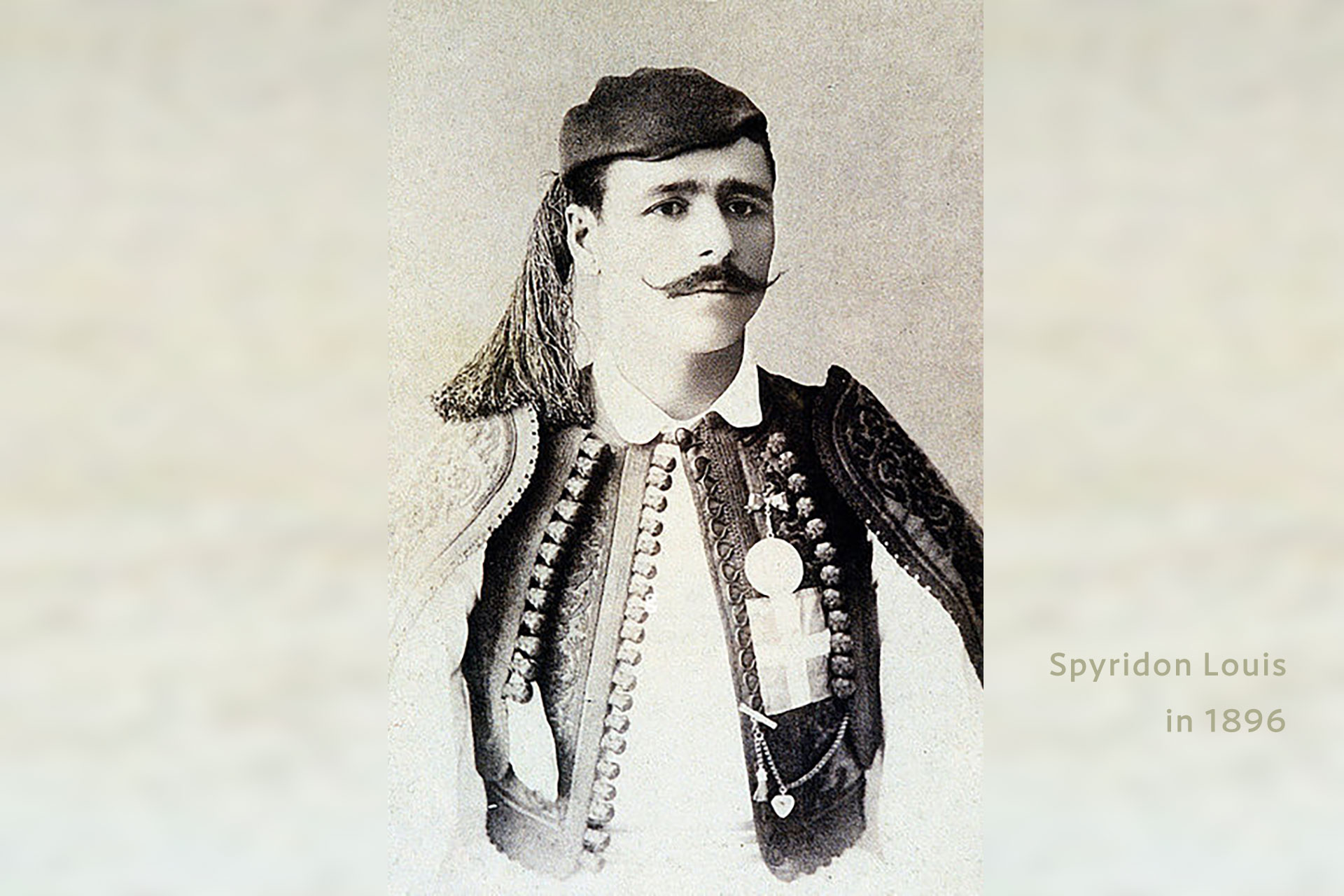

There is a legend that the original marathon was run in 490 BC by the soldier Pheidippides, a messenger hurrying from the Battle of Marathon to bring news of victory to Athens. The modern marathon, a distance of 42.195km, commemorates the distance he ran between Marathon and Athens. In 1896 Greeks rejoiced when their compatriot, Spyridon Louis, won the first official marathon. Louis was a humble water carrier, and apparently he stopped partway through the marathon to refresh himself with a glass of wine. His story shows how sport used to be more easy-going; today’s professional athletes would not be able to compete in this style!

Women and running

Women, unless they were priestesses, were not allowed to attend the ancient Olympics. This exclusion of women also occurred in modern times; no female athletes competed in the 1896 Olympics. Women were, however, allowed to take part in the second modern Olympics (in 1900 in Paris), although there were only 22 of them.

You may be surprised to learn how difficult it was for women to run in the Olympics. In 1928 the International Olympic Committee (IOC) believed, mistakenly, that women collapsed if they ran 800m, and did not permit them to run races longer than 200m. Women were also barred from competing in Olympic marathons until 1984. Kathrine Switzer became the first woman competitor in the 1967 Boston Marathon. Because she had registered with her usual signature, using just her initials, the race organisers didn’t realise that Switzer was a woman. When the race manager saw her running he was furious, and attacked Switzer and her trainer. She nevertheless managed to finish the race, determined to prove to the world that women were capable of running marathons. As a result of her unpleasant experience she campaigned for women to be allowed to compete in long-distance races, and at last in 1981 the IOC decided to add a women’s marathon to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Sport and equality

We may not associate politics with sport, but the two often come together in the Olympics. Society’s discrimination against women, and other marginalised groups such as LGBTQ athletes and athletes of colour, is always reflected in the status of these disadvantaged groups in the Olympics. However, the Olympics sometimes work as a force for good to lessen prejudice and improve human rights. One example is Jesse Owens, the black American track and field athlete, whose brilliant tally of four gold medals in the 1936 Berlin Olympics resoundingly disproved the German leader Adolf Hitler’s racist theory of white people’s superiority.

The IOC’s Olympic Charter commits the Olympics to achieving gender equality, not just for athletes, but also for coaches, and the members of the IOC and national Olympic committees. The IOC states that, since 2012, “women have participated in every Olympic sport at the Games. All new sports to be included in the Games must contain women’s events.” Statistics show that 21.5% of athletes at the 1984 Sarajevo Olympics were women, and this percentage increased to 41% at the 2018 PyeongChang Olympics. Before the coronavirus pandemic struck, women athletes at the Olympics scheduled for this year were projected to be 48.8%, giving an almost equal number of female and male athletes.

Coubertin devised the Olympic motto “Citius, altius, fortius”, meaning “Faster, higher, stronger”. Given the influence the Olympics have beyond sport, what do you think about updating the motto to “Faster, higher, stronger, and fairer”?